Portal:History of science

The History of Science Portal

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as alchemy and astrology during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, classical antiquity, and the Middle Ages declined during the early modern period after the establishment of formal disciplines of science in the Age of Enlightenment.

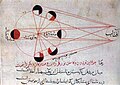

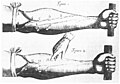

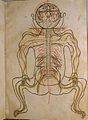

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3000 to 1200 BCE. These civilizations' contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced later Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages, but continued to thrive in the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the Hellenistic worldview was preserved and absorbed into the Arabic-speaking Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West. Traditions of early science were also developed in ancient India and separately in ancient China, the Chinese model having influenced Vietnam, Korea and Japan before Western exploration. Among the Pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica, the Zapotec civilization established their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics for producing calendars, followed by other civilizations such as the Maya.

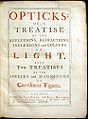

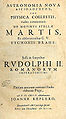

Natural philosophy was transformed during the Scientific Revolution in 16th- to 17th-century Europe, as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The New Science that emerged was more mechanistic in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined scientific method. More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The chemical revolution of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for chemistry. In the 19th century, new perspectives regarding the conservation of energy, age of Earth, and evolution came into focus. And in the 20th century, new discoveries in genetics and physics laid the foundations for new sub disciplines such as molecular biology and particle physics. Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science," particularly after World War II. (Full article...)

Selected article -

Nuclear fission was discovered in December 1938 by chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann and physicists Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch. Fission is a nuclear reaction or radioactive decay process in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller, lighter nuclei and often other particles. The fission process often produces gamma rays and releases a very large amount of energy, even by the energetic standards of radioactive decay. Scientists already knew about alpha decay and beta decay, but fission assumed great importance because the discovery that a nuclear chain reaction was possible led to the development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons. Hahn was awarded the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of nuclear fission.

Hahn and Strassmann at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin bombarded uranium with slow neutrons and discovered that barium had been produced. Hahn suggested a bursting of the nucleus, but he was unsure of what the physical basis for the results were. They reported their findings by mail to Meitner in Sweden, who a few months earlier had fled Nazi Germany. Meitner and her nephew Frisch theorised, and then proved, that the uranium nucleus had been split and published their findings in Nature. Meitner calculated that the energy released by each disintegration was approximately 200 megaelectronvolts, and Frisch observed this. By analogy with the division of biological cells, he named the process "fission". (Full article...)

Selected image

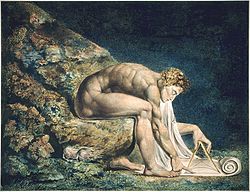

Poet and artist William Blake criticized Newton and like-minded philosophers such as Locke and Bacon for relying solely on reason.

Blake's 1795 print Newton is a demonstration of his opposition to the "single-vision" of scientific materialism: the great philosopher-scientist is shown utterly isolated in the depths of the ocean, his eyes (only one of which is visible) fixed on the compasses with which he draws on a scroll. His concentration is so fierce that he seems almost to become part of the rocks upon which he sits.

Did you know

...that in the history of paleontology, very few naturalists before the 17th century recognized fossils as the remains of living organisms?

...that on January 17, 2007, the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved to "5 minutes from midnight" in part because of global climate change?

...that in 1835, Caroline Herschel and Mary Fairfax Somerville became the first women scientists to be elected to the Royal Astronomical Society?

Selected Biography -

John Harrison (3 April [O.S. 24 March] 1693 – 24 March 1776) was an English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer, a long-sought-after device for solving the problem of how to calculate longitude while at sea.

Harrison's solution revolutionized navigation and greatly increased the safety of long-distance sea travel. The problem he solved had been considered so important following the Scilly naval disaster of 1707 that the British Parliament was offering financial rewards of up to £20,000 (equivalent to £3.97 million in 2024) under the 1714 Longitude Act, though Harrison never received the full reward due to political rivalries. He presented his first design in 1730, and worked over many years on improved designs, making several advances in time-keeping technology, finally turning to what were called sea watches. Harrison gained support from the Longitude Board in building and testing his designs. Towards the end of his life, he received recognition and a reward from Parliament. He came 39th in the BBC's 2002 public poll of the 100 Greatest Britons. (Full article...)

Selected anniversaries

- 1565 – Death of Lodovico Ferrari, Italian mathematician (b. 1522)

- 1713 – Birth of Denis Diderot, French philosopher and encyclopedist (d. 1784)

- 1777 – Death of Ján Andrej Segner, Slovak and German mathematician, physicist, and physician (b. 1704)

- 1781 – Birth of Bernard Bolzano, Czech mathematician and philosopher (d. 1848)

- 1882 – Birth of Robert Goddard, American rocket scientist (d. 1945)

- 1903 – Birth of M. King Hubbert, American geophysicist (d. 1989)

- 1905 - Wilbur Wright pilots Wright Flyer III in a flight of 24 miles in 39 minutes, a world record that stood until 1908

- 1976 – Death of Lars Onsager, Norwegian chemist, Nobel laureate (b. 1903)

- 1986 – Death of James H. Wilkinson, English mathematician (b. 1919)

- 2004 – Death of Maurice Wilkins, New Zealand physicist, Nobel laureate (b. 1916)

- 2004 – Death of William H. Dobelle, American biomedical engineer, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine nominee (b. 1941)

Related portals

Topics

General images

Subcategories

Things you can do

Help out by participating in the History of Science Wikiproject (which also coordinates the histories of medicine, technology and philosophy of science) or join the discussion.

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus