Timpani

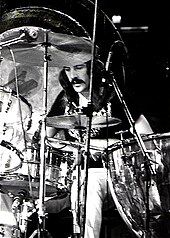

A timpanist | |

| Percussion instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Kettledrums, Timps, Pauken |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 211.11-922 (Struck membranophone with membrane lapped on by a rim) |

| Developed | at least c. 6th century AD |

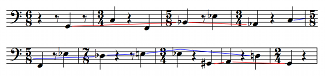

| Playing range | |

Ranges of individual sizes[1]  | |

| Related instruments | |

| Sound sample | |

|

| |

Timpani (/ˈtɪmpəni/;[2] Italian pronunciation: [ˈtimpani]) or kettledrums (also informally called timps)[2] are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionally made of copper. Thus timpani are an example of kettledrums, also known as vessel drums and semispherical drums, whose body is similar to a section of a sphere whose cut conforms the head. Most modern timpani are pedal timpani and can be tuned quickly and accurately to specific pitches by skilled players through the use of a movable foot-pedal. They are played by striking the head with a specialized beater called a timpani stick or timpani mallet. Timpani evolved from military drums to become a staple of the classical orchestra by the last third of the 18th century. Today, they are used in many types of ensembles, including concert bands, marching bands, orchestras, and even in some rock bands.

Timpani is an Italian plural, the singular of which is timpano. However, in English the term timpano is only widely in use by practitioners: several are more typically referred to collectively as kettledrums, timpani, temple drums, or timps. They are also often incorrectly termed timpanis. A musician who plays timpani is a timpanist.

Etymology and alternative spellings

[edit]First attested in English in the late 19th century, the Italian word timpani derives from the Latin tympanum (pl. tympana), which is the latinisation of the Greek word τύμπανον (tumpanon, pl. tumpana), 'a hand drum',[3] which in turn derives from the verb τύπτω (tuptō), meaning 'to strike, to hit'.[4] Alternative spellings with y in place of either or both i's—tympani, tympany, or timpany—are occasionally encountered in older English texts.[5] Although the word timpani has been widely adopted in the English language, some English speakers choose to use the word kettledrums.[6] The German word for timpani is Pauken; the Swedish word is pukor in plural (from the word puka), the French and Spanish is timbales, not to be confused with the latin percussion instrument, which would actually supersede the timpani in the traditional Cuban ensemble known as Charanga.[7]

The tympanum is mentioned, along with a faux name origin, in the Etymologiae of St. Isidore of Seville:

Tympanum est pellis vel corium ligno ex una parte extentum. Est enim pars media symphoniae in similitudinem cribri. Tympanum autem dictum quod medium est, unde et margaritum medium tympanum dicitur; et ipsud ut symphonia ad virgulam percutitur.[8]

The tympanum is a skin or hide stretched over one end of a wooden frame. It is half of a symphonia (i.e. another type of drum) and it looks like a sieve. The tympanum is so named because it is a half, whence also the half-pearl is called a tympanum. Like the symphonia, it is struck with a drumstick.[9]

The reference comparing the tympanum to half a pearl is borrowed from Pliny the Elder.[10]

Construction

[edit]Basic timpani

[edit]The basic timpano consists of a drum head stretched across the opening of a bowl typically made of copper[11] or, in less expensive models, fiberglass or aluminum. In the Sachs–Hornbostel classification, this makes timpani membranophones. The head is affixed to a hoop (also called a flesh hoop),[6][12] which in turn is held onto the bowl by a counter hoop.[6][13] The counter hoop is usually held in place with a number of tuning screws called tension rods placed regularly around the circumference. The head's tension can be adjusted by loosening or tightening the rods. Most timpani have six to eight tension rods.[11]

The shape and material of the bowl's surface help to determine the drum's timbre. For example, hemispheric bowls produce brighter tones while parabolic bowls produce darker tones.[14] Modern timpani are generally made with copper due to its efficient regulation of internal and external temperatures relative to aluminum and fiberglass.[15]

Timpani come in a variety of sizes from about 33 inches (84 cm) in diameter down to piccoli timpani of 12 inches (30 cm) or less.[6] A 33-inch drum can produce C2 (the C below the bass clef), and specialty piccoli timpani can play up into the treble clef. In Darius Milhaud's 1923 ballet score La création du monde, the timpanist must play F♯4 (at the bottom of the treble clef).

Each drum typically has a range of a perfect fifth, or seven semitones.[6]

Machine timpani

[edit]Changing the pitch of a timpani by turning each tension rod individually is a laborious process. In the late 19th century, mechanical systems to change the tension of the entire head at once were developed. Any timpani equipped with such a system may be considered machine timpani, although this term commonly refers to drums that use a handle connected to a spider-type tuning mechanism.[11]

Pedal timpani

[edit]By far the most common type of timpani used today are pedal timpani, which allows the tension of the head to be adjusted using a pedal mechanism. Typically, the pedal is connected to the tension screws via an assembly of either cast metal or metal rods called the spider.

There are three types of pedal mechanisms in common use today:

- The ratchet clutch system uses a ratchet and pawl to hold the pedal in place. The timpanist must first disengage the clutch before using the pedal to tune the drum. When the desired pitch is achieved, the timpanist must then reengage the clutch. Because the ratchet engages in only a fixed set of positions, the timpanist must fine-tune the drum by means of a fine-tuning handle.

- In the balanced action system, a spring or hydraulic cylinder is used to balance the tension on the head so the pedal will stay in position and the head will stay at pitch. The pedal on a balanced action drum is sometimes called a floating pedal since there is no clutch holding it in place.

- The friction clutch or post and clutch system uses a clutch that moves along a post. Disengaging the clutch frees it from the post, allowing the pedal to move without restraint.

Professional-level timpani use either the ratchet or friction system and have copper bowls. These drums can have one of two styles of pedals. The Dresden pedal is attached at the side nearest the timpanist and is operated by ankle motion. A Berlin-style pedal is attached by means of a long arm to the opposite side of the timpani, and the timpanist must use their entire leg to adjust the pitch. In addition to a pedal, high-end instruments have a hand-operated fine-tuner, which allows the timpanist to make minute pitch adjustments. The pedal is on either the left or right side of the drum depending on the direction of the setup.

Most school bands and orchestras below a university level use less expensive, more durable timpani with copper, fiberglass, or aluminum bowls. The mechanical parts of these instruments are almost completely contained within the frame and bowl. They may use any of the pedal mechanisms, though the balanced action system is by far the most common, followed by the friction clutch system. Many professionals also use these drums for outdoor performances due to their durability and lighter weight. The pedal is in the center of the drum itself.

Chain timpani

[edit]

On chain timpani, the tension rods are connected by a roller chain much like the one found on a bicycle, though some manufacturers have used other materials, including steel cable. In these systems, all the tension screws can then be tightened or loosened by one handle. Though far less common than pedal timpani, chain and cable drums still have practical uses. Occasionally, a timpanist is forced to place a drum behind other items, so he cannot reach it with his foot. Professionals may also use exceptionally large or small chain and cable drums for special low or high notes.

Other tuning mechanisms

[edit]A rare tuning mechanism allows the pitch to be changed by rotating the drum itself. A similar system is used on rototoms. Jenco, a company better known for mallet percussion, made timpani tuned in this fashion.

In the early 20th century, Hans Schnellar, the timpanist of the Vienna Philharmonic, developed a tuning mechanism in which the bowl is moved via a handle that connects to the base and the head remains stationary. These instruments are referred to as Viennese timpani (Wiener Pauken) or Schnellar timpani.[16] Adams Musical Instruments developed a pedal-operated version of this tuning mechanism in the early 21st century.

Heads

[edit]Like most drumheads, timpani heads can be made from two materials: animal skin (typically calfskin or goatskin)[6] or plastic (typically PET film). Plastic heads are durable, weather-resistant, and relatively inexpensive. Thus, they are more commonly used than skin heads. However, many professional timpanists prefer skin heads because they produce a "warmer" timbre. Timpani heads are determined based on the size of the head, not the bowl. For example, a 23-inch (58 cm) drum may require a 25-inch (64 cm) head. This 2-inch (5 cm) size difference has been standardized by most timpani manufacturers since 1978.[17]

Sticks and mallets

[edit]

Timpani are typically struck with a special type of drum stick called a timpani stick or timpani mallet. Timpani sticks are used in pairs. They have two components: a shaft and a head. The shaft is typically made from hardwood or bamboo but may also be made from aluminum or carbon fiber. The head can be constructed from a number of different materials, though felt wrapped around a wooden core is the most common. Other core materials include compressed felt, cork, and leather.[18] Unwrapped sticks with heads of wood, felt, flannel, and leather are also common.[6] Wooden sticks are used as a special effect[19]—specifically requested by composers as early as the Romantic era—and in authentic performances of Baroque music. Wooden timpani sticks are also occasionally used to play the suspended cymbal.

Although not usually stated in the score (excepting the occasional request to use wooden sticks), timpanists will change sticks to suit the nature of the music. However, the choice during a performance is subjective and depends on the timpanist's preference and occasionally the wishes of the conductor. Thus, most timpanists own a great number of sticks.[6] The weight of the stick, size and latent surface area of the head, materials used for the shaft, core, and wrap, and method used to wrap the head all contribute to the timbre the stick produces.[20]

In the early 20th century and before, sticks were often made with whalebone shafts, wooden cores, and sponge wraps. Composers of that era often specified sponge-headed sticks. Modern timpanists execute such passages with felt sticks.

Popular grips

[edit]The two most common grips in playing the timpani are the German and French grips. In the German grip, the palm of the hand is approximately parallel with the drum head and the thumb should be on the side of the stick. In the French grip, the palm of the hand is approximately perpendicular with drum head and the thumb is on top of the stick. In both of these styles, the fulcrum is the contact between the thumb and middle finger. The index finger is used as a guide and to help lift the stick off of the drum.[21] The American grip is a hybrid of these two grips. Another known grip is known as the Amsterdam Grip, made famous by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, which is similar to the Hinger grip, except the stick is cradled on the lower knuckle of the index finger.

In the modern ensemble

[edit]

Standard set

[edit]A standard set of timpani (sometimes called a console) consists of four drums: roughly 32 inches (81 cm), 29 inches (74 cm), 26 inches (66 cm), and 23 inches (58 cm) in diameter.[22] The range of this set is roughly D2 to A3. A great majority of the orchestral repertoire can be played using these four drums. However, contemporary composers have written for extended ranges. Igor Stravinsky specifically writes for a piccolo timpano in The Rite of Spring, tuned to B3. A piccolo drum is typically 20 inches (51 cm) in diameter and can reach pitches up to C4.

Beyond this extended set of five instruments, any added drums are nonstandard. (Luigi Nono's Al gran sole carico d'amore requires as many as eleven drums, with actual melodies played on them in octaves by two players.) Many professional orchestras and timpanists own more than just one set of timpani, allowing them to execute music that cannot be more accurately performed using a standard set of four or five drums. Many schools and youth orchestra ensembles unable to afford purchase of this equipment regularly rely on a set of two or three timpani, sometimes referred to as "the orchestral three".[6] It consists of 29-inch (74 cm), 26-inch (66 cm), and 23-inch (58 cm) drums. Its range extends down only to F2.

The drums are set up in an arc around the performer. Traditionally, North American, British, and French timpanists set their drums up with the lowest drum on the left and the highest on the right (commonly called the American system), while German, Austrian, and Greek players set them up in the reverse order, as to resemble a drum set or upright bass (the German system).[6] This distinction is not strict, as many North American players use the German setup and vice versa.

Players

[edit]

Throughout their education, timpanists are trained as percussionists, and they learn to play all instruments of the percussion family along with timpani. However, when appointed to a principal timpani chair in a professional ensemble, a timpanist is not normally required to play any other instruments. In his book Anatomy of the Orchestra, Norman Del Mar writes that the timpanist is "king of his own province", and that "a good timpanist really does set the standard of the whole orchestra." A qualified member of the percussion section sometimes doubles as associate timpanist, performing in repertoire requiring multiple timpanists and filling in for the principal timpanist when required.

Among the professionals who have been highly regarded for their virtuosity and impact on the development of the timpani in the 20th century are Saul Goodman, Hans Schnellar, Fred Hinger, Tom Freer, and Cloyd Duff.[23][24][25]

Concertos

[edit]A few solo concertos have been written for timpani, and are for timpani and orchestral accompaniment. The 18th-century composer Johann Fischer wrote a symphony for eight timpani and orchestra, which requires the solo timpanist to play eight drums simultaneously. Rough contemporaries Georg Druschetzky and Johann Melchior Molter also wrote pieces for timpani and orchestra. Throughout the 19th century and much of the 20th, there were few new timpani concertos. In 1983, William Kraft, principal timpanist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, composed his Concerto for Timpani and Orchestra, which won second prize in the Kennedy Center Friedheim Awards. There have been other timpani concertos, notably, Philip Glass, considered one of the most influential composers of the late 20th century,[26] wrote a double concerto at the behest of soloist Jonathan Haas titled Concerto Fantasy for Two Timpanists and Orchestra, which features its soloists playing nine drums a piece.[27]

Performance techniques

[edit]Striking

[edit]For general playing, a timpanist will beat the head approximately 4 inches (10 cm) in from the edge.[22] Beating at this spot produces the round, resonant sound commonly associated with timpani. A timpani roll (most commonly signaled in a score by tr or three slashes) is executed by striking the timpani at varying velocities; the speed of the strokes are determined by the pitch of the drum, with higher pitched timpani requiring a quicker roll than timpani tuned to a lower pitch. While performing the timpani roll, mallets are usually held a few inches apart to create more sustain.[28] Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 7 requires a continuous roll on a drum for over two and a half minutes. In general, timpanists do not use multiple bounce rolls like those played on the snare drum, as the soft nature of timpani sticks causes the rebound of the stick to be reduced, causing multiple bounce rolls to sound muffled.[6] However, when playing with wood mallets, timpanists sometimes use multiple bounce rolls.[29]

The tone quality can be altered without switching sticks or adjusting the tuning. For example, by playing closer to the edge, the sound becomes thinner.[6] A more staccato sound can be produced by changing the velocity of the stroke or playing closer to the center.[28]

Tuning

[edit]Prior to playing, the timpanist must clear the heads by equalizing the tension at each tuning screw. This is done so every spot is tuned to exactly the same pitch. When the head is clear, the timpani will produce an in-tune sound. If the head is not clear, the pitch will rise or fall after the initial impact of a stroke, and the drum will produce different pitches at different dynamic levels. Timpanists are required to have a well-developed sense of relative pitch and must develop techniques to tune in an undetectable manner and accurately in the middle of a performance. Tuning is often tested with a light tap from a finger, which produces a near-silent note.

Some timpani are equipped with tuning gauges, which provide a visual indication of the pitch. They are physically connected either to the counterhoop, in which case the gauge indicates how far the counterhoop is pushed down, or the pedal, in which case the gauge indicates the position of the pedal. These gauges are accurate when used correctly. However, when the instrument is disturbed in some fashion (transported, for example), the overall pitch can change, thus the markers on the gauges may not remain reliable unless they have been adjusted immediately preceding the performance. The pitch can also be changed by room temperature and humidity. This effect also occurs due to changes in weather, especially if an outdoor performance is to take place. Gauges are especially useful when performing music that involves fast tuning changes that do not allow the timpanist to listen to the new pitch before playing it. Even when gauges are available, good timpanists will check their intonation by ear before playing. Occasionally, timpanists use the pedals to retune while playing.

Portamento effects can be achieved by changing the pitch while it can still be heard. This is commonly called a glissando, though this use of the term is not strictly correct. The most effective glissandos are those from low to high notes and those performed during rolls. One of the first composers to call for a timpani glissando was Carl Nielsen, who used two sets of timpani playing glissandos at the same time in his Symphony No. 4 ("The Inextinguishable").

Pedaling refers to changing the pitch with the pedal; it is an alternate term for tuning. In general, timpanists reserve this term for passages where they must change the pitch in the midst of playing. Early 20th-century composers such as Nielsen, Béla Bartók, Samuel Barber, and Richard Strauss took advantage of the freedom that pedal timpani afforded, often giving the timpani the bass line.

Muffling

[edit]Since timpani have a long sustain, muffling or damping is an inherent part of playing. Often, timpanists will muffle notes so they only sound for the length indicated by the composer. However, early timpani did not resonate nearly as long as modern timpani, so composers often wrote a note when the timpanist was to hit the drum without concern for sustain. Today, timpanists must use their ear and the score to determine the length the note should sound.

The typical method of muffling is to place the pads of the fingers against the head while holding onto the timpani stick with the thumb and index finger. Timpanists are required to develop techniques to stop all vibration without making any sound from the contact of their fingers.[22]

Muffling is often referred to as muting, which can also refer to playing with mutes on them (see below).

Extended techniques

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

It is typical for only one timpani to be struck at a time, but occasionally composers will ask for two notes. This is called a double stop, a term borrowed from the string instrument vocabulary. Ludwig van Beethoven uses this effect in the slow third movement of his Ninth Symphony, as do Johannes Brahms in the second movement of his German Requiem and Aaron Copland in El Salón México. Some modern composers occasionally require more than two notes. In this case, a timpanist can hold two sticks in one hand much like a marimbist, or more than one timpanist can be employed. In his Overture to Benvenuto Cellini, for example, Hector Berlioz realizes fully voiced chords from the timpani by requiring three timpanists and assigning one drum to each. He goes as far as ten timpanists playing three- and four-part chords on sixteen drums in his Requiem, although with the introduction of pedal tuning, this number can be reduced.

Modern composers will often specify the beating spot to alter the sound of the drum. When the timpani are struck directly in the center, they have a sound that is almost completely devoid of tone and resonance. George Gershwin uses this effect in An American in Paris. Struck close to the edge, timpani produce a very thin, hollow sound. This effect is used by composers such as Bartók, Bernstein, and Kodály.

A variation of this is to strike the head while two fingers of one hand lightly press and release spots near the center. The head will then vibrate at a harmonic much like the similar effect on a string instrument.

Resonance can cause timpani not in use to vibrate, causing a quieter sound to be produced. Timpanists must normally avoid this effect, called sympathetic resonance, but composers have exploited it in solo pieces such as Elliott Carter's Eight Pieces for Four Timpani. Resonance is reduced by damping or muting the drums, and in some cases composers will specify that timpani be played con sordino (with mute) or coperti (covered), both of which indicate that mutes – typically small pieces of felt or leather – should be placed on the head.

Composers will sometimes specify that the timpani should be struck with implements other than timpani sticks. It is common in timpani etudes and solos for timpanists to play with their hands or fingers. Philip Glass's Concerto Fantasy utilizes this technique during a timpani cadenza. Also, Michael Daugherty's Raise The Roof calls for this technique to be used for a certain passage. Leonard Bernstein calls for maracas on timpani in his Symphony No. 1 Jeremiah and in his Symphonic Dances from West Side Story suite. Edward Elgar attempts to use the timpani to imitate the engine of an ocean liner in his Enigma Variations by requesting the timpanist play a soft roll with snare drum sticks. However, snare drum sticks tend to produce too loud a sound, and since this work's premiere, the passage has been performed by striking with coins. Benjamin Britten asks for the timpanist to use drumsticks in his War Requiem to evoke the sound of a field drum.

Robert W. Smith's Songs of Sailor and Sea calls for a "whale sound" on the timpani. This is achieved by moistening the thumb and rubbing it from the edge to the center of the head. Among other techniques used primarily in solo work, such as John Beck's Sonata for Timpani, is striking the bowls. Timpanists tend to be reluctant to strike the bowls at loud levels or with hard sticks since copper can be dented easily due to its soft nature.

On some occasions a composer may ask for a metal object, commonly an upside-down cymbal, to be placed upon the head and then struck or rolled while executing a glissando on the drum. Joseph Schwantner uses this technique in From A Dark Millennium. Carl Orff asks for cymbals resting on the head while the drum is struck in his later works. Additionally, Michael Daugherty utilizes this technique in his concerto Raise The Roof. In his piece From me flows what you call Time, Tōru Takemitsu calls for Japanese temple bowls to be placed on timpani.[30]

History

[edit]

Pre-orchestral history

[edit]The first recorded use of early Tympanum was in "ancient times when it is known that they were used in religious ceremonies by Hebrews."[22] The Moon of Pejeng, also known as the Pejeng Moon,[31] in Bali, the largest single-cast bronze kettledrum in the world,[32] is more than two thousand years old.[33] The Moon of Pejeng is "the largest known relic from Southeast Asia's Bronze Age period."[34] The drum is in the Pura Penataran Sasih temple."[35]

In 1188, Cambro-Norman chronicler Gerald of Wales wrote, "Ireland uses and delights in two instruments only, the harp namely, and the tympanum."[36]

Arabian nakers, the direct ancestors of most timpani, were brought to 13th-century Continental Europe by Crusaders and Saracens.[11] These drums, which were small (with a diameter of about 8 to 8+1⁄2 inches (20–22 cm)) and mounted to the player's belt, were used primarily for military ceremonies. This form of timpani remained in use until the 16th century. In 1457, a Hungarian legation sent by King Ladislaus V carried larger timpani mounted on horseback to the court of King Charles VII in France. This variety of timpani had been used in the Middle East since the 12th century. These drums evolved together with trumpets to be the primary instruments of the cavalry. This practice continues to this day in sections of the British Army, and timpani continued to be paired with trumpets when they entered the classical orchestra.[37]

The medieval European timpani were typically put together by hand in the southern region of France. Some drums were tightened together by horses tugging from each side of the drum by the bolts. Over the next two centuries, a number of technical improvements were made to the timpani. Originally, the head was nailed directly to the shell of the drum. In the 15th century, heads began to be attached and tensioned by a counterhoop tied directly to the shell. In the early 16th century, the bindings were replaced by screws. This allowed timpani to become tunable instruments of definite pitch.[6] The Industrial Revolution enabled the introduction of new construction techniques and materials, in particular machine and pedal tuning mechanisms. Plastic heads were introduced in the mid-20th century, led by Remo.[38]

Role in orchestra

[edit]"No written kettledrum music survives from the 16th century, because the technique and repertory were learned by oral tradition and were kept secret. An early example of trumpet and kettledrum music occurs at the beginning of Claudio Monteverdi's opera L'Orfeo (1607)."[39] Later in the Baroque era, Johann Sebastian Bach wrote a secular cantata titled Tönet, ihr Pauken! Erschallet, Trompeten!, which translates roughly to "Sound off, ye timpani! Sound, trumpets!" Naturally, the timpani are placed at the forefront: the piece starts with an unusual timpani solo and the chorus and timpani trade the melody back and forth. Bach reworked this movement in Part I of the Christmas Oratorio.

Mozart and Haydn wrote many works for the timpani and even started putting it in their symphonies and other orchestral works.

Ludwig van Beethoven revolutionized timpani music in the early 19th century. He not only wrote for drums tuned to intervals other than a fourth or fifth, but he gave a prominence to the instrument as an independent voice beyond programmatic use. For example, his Violin Concerto (1806) opens with four solo timpani strokes, and the scherzo of his Ninth Symphony (1824) sets the timpani (tuned an octave apart) against the orchestra in a sort of call and response.[40]

The next major innovator was Hector Berlioz. He was the first composer to indicate the exact sticks that should be used—"felt-covered", "wooden", etc. In several of his works, including Symphonie fantastique (1830), and his Requiem (1837), he demanded the use of several timpanists at once.[22]

Until the late 19th century, timpani were hand-tuned; that is, there was a sequence of screws with T-shaped handles, called taps, which altered the tension in the head when turned by players. Thus, tuning was a relatively slow operation, and composers had to allow a reasonable amount of time for players to change notes if they were called to tune in the middle of a work. The first 'machine' timpani, with a single tuning handle, was developed in 1812.[41] The first pedal timpani originated in Dresden in the 1870s and are called Dresden timpani for this reason.[11] However, since vellum was used for the heads of the drums, automated solutions were difficult to implement since the tension would vary unpredictably across the drum. This could be compensated for by hand-tuning, but not easily by a pedal drum. Mechanisms continued to improve in the early 20th century.

Despite these problems, composers eagerly exploited the opportunities the new mechanism had to offer. By 1915, Carl Nielsen was demanding glissandos on timpani in his Fourth Symphony—impossible on the old hand-tuned drums. However, it took Béla Bartók to more fully realize the flexibility the new mechanism had to offer. Many of his timpani parts require such a range of notes that it would be unthinkable to attempt them without pedal drums.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, timpani were almost always tuned with the dominant note of the piece on the low drum and the tonic on the high drum—a perfect fourth apart. Until the early 19th century the dominant (the note of the large drum) was written as G and the tonic (the note of the small drum) was written as C no matter what the actual key of the work was, and whether it was major or minor, with the actual pitches indicated at the top of the score (for example, Timpani in D–A for a work in D major or D minor).[11] This notation style however was not universal: Bach, Mozart, and Schubert (in his early works) used it, but their respective contemporaries Handel, Haydn, and Beethoven wrote for the timpani at concert pitch.[42]

In the 2010s, even though they are written at concert pitch, timpani parts continue to be most often[43] but not always[44] written with no key signature, no matter what key the work is in: accidentals are written in the staff, both in the timpanist's part and the conductor's score. By 1977 in Vienna, Alexander Rahbari, an outstanding Iranian-Austrian composer and conductor, commenced the concert with one of his own compositions, entitled Persian Mysticism Around G, which starts with a short introduction written for timpani (five timpani tuned in B♭-C-D-E♭-G). After a few bars fomenting the primary stormy passage, he uses an effective glissando effect produced by the back and forth switching of the timpani pedals, moving from B♭ up to C and then rolling down back to G (You can see the glissando notation and also listen to the whole timpani introduction on the right).[45] Rahbari also makes use of a series of acciaccatura during this opening section.

Outside the orchestra

[edit]

Later, timpani were adopted into other classical music ensembles such as concert bands. In the 1970s, marching bands and drum and bugle corps, which evolved both from traditional marching bands and concert bands, began to include marching timpani. Unlike concert timpani, marching versions had fiberglass shells to make them light enough to carry. Each player carried a single drum, which was tuned by a hand crank. Often, during intricate passages, the timpani players would put their drums on the ground by means of extendable legs, and perform more like conventional timpani, yet with a single player per drum. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, marching arts-based organizations' allowance for timpani and other percussion instruments to be permanently grounded became mainstream. This was the beginning of the end for marching timpani: eventually, standard concert timpani found their way onto the football field as part of the front ensemble, and marching timpani fell out of common usage. Timpani are still used by the Mounted Bands of the Household Division of the British Army[46] and of the Mounted Band of the Garde Républicaine in the French Army.

As rock and roll bands started seeking to diversify their sound, timpani found their way into the studio. In 1959 Leiber and Stoller made the innovative use of timpani in their production of the Drifters' recording, "There Goes My Baby." Starting in the 1960s, drummers for high-profile rock acts like The Beatles, Cream, Led Zeppelin, The Beach Boys, and Queen incorporated timpani into their music.[47] This led to the use of timpani in progressive rock. Emerson, Lake & Palmer recorded a number of rock covers of classical pieces that utilize timpani. Rush drummer Neil Peart added a tympani to his expanding arsenal of percussion for the Hemispheres (1978) and Permanent Waves (1980) albums and tours, and would later sample tympani in his drum solo, "The Rhythm Method" in 1988. More recently, the rock band Muse has incorporated timpani into some of their classically based songs, most notably in Exogenesis: Symphony, Part I (Overture). Jazz musicians also experimented with timpani. Sun Ra used it occasionally in his Arkestra (played, for example, by percussionist Jim Herndon on the songs "Reflection in Blue" and "El Viktor," both recorded in 1957). In 1964, Elvin Jones incorporated timpani into his drum kit on John Coltrane's four-part composition A Love Supreme. Butch Trucks, drummer with the Allman Brothers Band, made use of the timpani.

In his choral piece A Stopwatch and an Ordnance Map,[48] Samuel Barber employs three pedal timpani upon which are played glissandos.

Jonathan Haas is one of the few timpanists who markets himself as a soloist. Haas, who began his career as a solo timpanist in 1980, is notable for performing music from many genres including jazz, rock, and classical. He released an album with a rather unconventional jazz band called Johnny H. and the Prisoners of Swing. Philip Glass[49] with his Concerto Fantasy, commissioned by Haas, put two soloists in front of the orchestra, an atypical placement for the instruments. Haas also commissioned Susman's Floating Falling for timpani and cello.[50]

See also

[edit]- Lytavry

- Electronic tuner

- List of timpani manufacturers

- Missing fundamental

- Vibrations of a drum head

- Davul

References

[edit]- ^ Samuel Z. Solomon, "How to Write for Percussion", pp. 65–66. Published by the author, 2002. ISBN 0-9744721-0-7

- ^ a b "timpani". www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com.

- ^ τύμπανον, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ τύπτω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ "Tympani, Tympanist". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Grove, George (January 2001). Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Encyclopædia of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). Grove's Dictionaries of Music. Volume 18, pp826–837. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Charley Gerard (2001). Music from Cuba: Mongo Santamaria, Chocolate Armenteros, and Other Stateside Cuban Musicians. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 67. ISBN 9780275966829. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae 3.22.10, Bill Thayer's edition of the Latin text at LacusCurtius online.

- ^ Barney, Stephen (2010). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge University Press. p. 98.

- ^ Natural History IX. 35, 23. Quoted in Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 289.

- ^ a b c d e f Bridge, Robert. "Timpani Construction paper" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ "Definition of FLESH HOOP". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "Definition of COUNTER HOOP". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Power, Andrew (April 1983). "Sound Production of the Timpani, Part 1". Percussive Notes. 21 (4). Percussive Arts Society: 62–64.

- ^ Jones, Richard K. (March 2017). "In Search of the Missing Fundamental". The Well-Tempered Timpani. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ Vibration patterns and sound analysis of the Viennese Timpani. Bertsch, Matthias. (2001), Proceedings of ISMA 2001

- ^ "Timpani Head Guide", Steve Weiss Music

- ^ Kallen, Stuart (2003). "One". The Instruments of Music. Farmington Hills, MI: Lucent Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-59018-127-0. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ "T5 Wood". Vic Firth. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ Slow Motion of Timpani Technique | Percussion Research. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Hoffman, Stewart. "Playing Timpani | Timpani Techniques | High School Percussion". stewarthoffmanmusic.com. Toronto, ON: Stewart Hoffman Music. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Goodman, Saul (1988) [1948]. Modern Method for Tympani. Van Nuys, California: Alfred Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7579-9100-4.

- ^ "Wiener Pauken – handmade timpani of Anton Mittermayr – timpani builder of Wiener Philharmoniker". www.wienerpauken.at.

- ^ "Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame: Fred Hinger". Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Atwood, Jim. "Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame: Cloyd Duff". Pas.org. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ O'Mahony, John (24 November 2001), "The Guardian Profile: Philip Glass", The Guardian, London, retrieved 14 December 2015

- ^ "Concerto Fantasy for Two Timpanists and Orchestra" Archived 20 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Philip Glass Official Website

- ^ a b Jones, Brett (19 November 2013). "Percussion Performance:Timpani". School Band and Orchestra. Las Vegas, Nevada: Timeless Communications. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "How and When to Play a Buzz Roll on Timpani". freepercussionlessons.com. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "From me flows what you call Time". englisch. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ For a thorough scholarly analysis of the Pejeng Moon and the type of drum named after it, see August Johan Bernet Kempers, "The Pejeng type," The Kettledrums of Southeast Asia: A Bronze Age World and Its Aftermath (Taylor & Francis, 1988), 327–340.

- ^ Iain Stewart and Ryan Ver Berkmoes, Bali & Lombok (Lonely Planet, 2007), 203.

- ^ Yayasan Bumi Kita and Anne Gouyon, The Natural Guide to Bali: Enjoy Nature, Meet the People, Make a Difference (Tuttle Publishing, 2005), 109.

- ^ Pringle, Robert (2004). Bali: Indonesia's Hindu Realm; A short history of. Short History of Asia Series. Allen & Unwin. pp. 28–40. ISBN 978-1-86508-863-1.

- ^ Rita A. Widiadana, "Get in touch with Bali's cultural heritage Archived 5 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine," The Jakarta Post (6 June 2002).

- ^ Topographia Hibernica, III.XI; tr. O'Meary, p. 94.

- ^ Seaman, Christopher; Richards, Michael (2013). Inside Conducting (1st ed.). Rochester: University of Rochester Press, Boydell & Brewer. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-1-58046-411-6. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt3fgm4p.2.

- ^ "Company". Remo Inc. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ "Kettledrum; Musical Instrument". Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 August 2014.

- ^ Krentzer, Bill (December 1969). "The Beethoven Symphonies: Innovations of an Original Style in Timpani Scoring". Percussionist. 7 (2). Percussive Arts Society: 55–62.

- ^ Bowles, Edmund A. (1999). "The Impact of Technology on Musical Instruments". COSMOS Journal. Cosmos Club. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ Del Mar, Norman (1981). The Anatomy of the Orchestra. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04500-9.[page needed]

- ^ See, as an early 20th-century example, the orchestral score of Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande: through no. 6 non-transposing parts have a key signature of one flat but the timpani part has no key signature, in bar 7 of no. 1 the timpani B♭ is written in the staff; nos. 29 to 30 non-transposing parts have a key signature of four sharps but, again, the timpani part has no key signature, and so on.

- ^ For an example where this is not done, i.e. where the timpani part carries the same signature as all the other parts, see the orchestral score of Prokofiev's Piano Concerto No. 1 in D♭ major, where, incidentally, transposing instrument parts are also written at concert pitch with the same key signature as all the other parts.

- ^ "Persian Mysticism". youtube.com. 3 February 2020. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021.

- ^ Beating Retreat page, showing image of mounted bands with timpani in 2008.

- ^ McNamee, David (27 April 2009). "Hey, what's that sound: Timpani". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ "Samuel Barber – 'A Stopwatch and an Ordnance Map'". YouTube. 2 January 2017. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Philip Glass". philipglass.com.

- ^ ""Susman-Floating Falling"". Steve Weiss Music.

Further reading

[edit]- Adler, Samuel. The Study of Orchestration. W. W. Norton & Company, 3rd edition, 2002. ISBN 0-393-97572-X

- Del Mar, Norman. Anatomy of the Orchestra. University of California Press, 1984. ISBN 0-520-05062-2

- Ferrell, Robert G. "Percussion in Medieval and Renaissance Dance Music: Theory and Performance". 1997. Retrieved 22 February 2006.

- Montagu, Jeremy. Timpani & Percussion. Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-300-09337-3

- Peters, Mitchell. Fundamental Method for Timpani. Alfred Publishing Co., 1993. ISBN 0-7390-2051-X

- Solomon, Samuel Z. How to Write for Percussion. Published by the author, 2002. ISBN 0-9744721-0-7

- Thomas, Dwight. Timpani: Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved 4 February 2005.

- "Credits: Beatles for Sale". Allmusic. Retrieved 18 February 2005.

- "Credits: A Love Supreme". Allmusic. Retrieved 18 February 2005.

- "Credits: Tubular Bells". Allmusic. Retrieved 18 February 2005.

- "William Kraft Biography". Composer John Beal. Retrieved 21 May 2006.

- "Timpanist – Musician or Technician?". Cloyd E. Duff, Principal Timpani – retired – Cleveland Orchestra.

- "Timpani" Grove, George (January 2001). Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Encyclopædia of Music and Musicians. Vol. 18 (2nd ed.). Grove's Dictionaries of Music. 826–837. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of timpani at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of timpani at Wiktionary Media related to Timpani at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Timpani at Wikimedia Commons- The Well-Tempered Timpani—Timpani harmonics information

- Website of Guido Rückel, solo-timpanist of Munich Philharmonic; many timpani pictures

- Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 763–766.

- "534m Membranophones". SIL. Archived from the original on 10 July 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2007.