Fatehpur Sikri

Fatehpur Sikri | |

|---|---|

Town | |

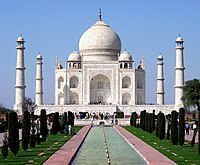

Buland Darwaza, the 54-metre-high (177 ft) entrance to Fatehpur Sikri's Jama Masjid | |

| Coordinates: 27°05′28″N 77°39′40″E / 27.091°N 77.661°E | |

| Country | India |

| State | Uttar Pradesh |

| District | Agra |

| Founded by | Akbar |

| Population | |

• Total | 32,905 |

| Language | |

| • Official | Hindi[2] |

| • Additional official | Urdu[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| Vehicle registration | UP-80 |

| Official name | Fatehpur Sikri |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 255 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

Fatehpur Sikri (Hindi: [ˈfətɛɦpʊɾ ˈsiːkɾiː]) is a town in the Agra District of Uttar Pradesh, India. Situated 35.7 kilometres (22.2 mi) from the district headquarters of Agra,[3] Fatehpur Sikri itself was founded as the capital of the Mughal Empire in 1571 by Emperor Akbar, serving this role from 1571 to 1585, when Akbar abandoned it due to a campaign in Punjab and was later completely abandoned in 1610.[4]

The name of the city is derived from the village called Sikri which previously occupied the location. An Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) excavation from 1999 to 2000 indicated that there was housing, temples and commercial centres here before Akbar built his capital. The region was settled by Sungas following their expansion. It was controlled by Sakarwar Rajputs from the 7th to 16th century CE until the Battle of Khanwa (1527).[5]

The khanqah of Sheikh Salim Chishti existed earlier at this place. Akbar's son, Jahangir, was born in the village of Sikri to his favourite wife Mariam-uz-Zamani in 1569,[6] and, in that year, Akbar began construction of a religious compound to commemorate the Sheikh who had predicted the birth. After Jahangir's second birthday, he began the construction of a walled city and imperial palace here. The city came to be known as Fatehpur Sikri, the "City of Victory", after Akbar's victorious Gujarat campaign in 1573.

After occupying Agra in 1803, the East India Company established an administrative centre here and it remained so until 1850. In 1815, the Marquess of Hastings ordered the repair of monuments at Sikri.

Because of its historical importance as the capital of the Mughal Empire and its outstanding architecture, Fatehpur Sikri was awarded the status of UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986.[7][8]

History

[edit]Archaeological evidence points to settlement of the region since the Painted Grey Ware period. According to historian Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi, the region flourished under Sunga rule and then under Sikarwar Rajputs, who built a fortress when they controlled the area from 7th to 16th century, until the Battle of Khanwa (1527). The area later came under the rule of the Delhi Sultanate and many mosques were built at the place which grew in size during the period of the Khalji dynasty.[9][10]

Basing his arguments on the excavations by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1999–2000 at the Chabeli Tila, senior Agra journalist Bhanu Pratap Singh said the antique pieces, statues, and structures all point to a lost "culture and religious site," more than 1,000 years ago. "The excavations yielded a rich crop of Jain statues, hundreds of them, including the foundation stone of a temple with the date. The statues were a thousand years old of Bhagwan Adi Nath, Bhagwan Rishabh Nath, Bhagwan Mahavir and Jain Yakshinis," said Swarup Chandra Jain, senior leader of the Jain community. Historian Sugam Anand states that there is proof of habitation, temples and commercial centres even before Akbar established it as his capital. He states that the open space on a ridge was used by Akbar to build his capital.[11][12][13]

But preceding Akbar's appropriation of the site for his capital city, his predecessors Babur and Humayun did much to redesign Fatehpur Sikri's urban layout.[14] Attilio Petruccioli, a scholar of Islamic architecture and Professor of Landscape Architecture at the Polytechnic University of Bari, Italy, notes that "Babur and his successors" wanted "to get away from the noise and confusion of Agra [and] build an uninterrupted sequence of gardens on the free left bank of the Yamuna, linked both by boat and by land."[14] Petruccioli adds that when such escapist landscapes are envisioned, the monument becomes the organising element of the city at large, partly due to its orientation at a significant location and partly due to its sheer size. Buland Darwaza was one such organising element, which at a height of 150 feet towered over the city and is now one of the most recognisable Mughal monuments in the country.[14]

The place was much loved by Babur, who called it Shukri (Thanks), after its large lake that was used by Mughal armies.[15] Annette Beveridge in her translation of Baburnama noted that Babur points "Sikri" to read "Shukri".[16] Per his memoirs, Babur constructed a garden here called the "Garden of Victory" after defeating Rana Sangha at its outskirts. Gulbadan Begum's Humayun-Nama describes that in the garden he built an octagonal pavilion which he used for relaxation and writing. In the center of the nearby lake, he built a large platform. A baoli exists at the base of a rock scarp about a kilometre from the Hiran Minar. This was probably the original site of a well-known epigraph commemorating his victory.[15]

Abul Fazl records Akbar's reasons for the foundation of the city in Akbarnama: "In as much as his exalted sons (Salim and Murad) had been born at Sikri, and the God-knowing spirit of Shaikh Salim had taken possession thereof, his holy heart desired to give outward splendour to this spot which possessed spiritual grandeur. Now that his standards had arrived at this place, his former design was pressed forward, and an order was issued that the superintendents of affairs should erect lofty buildings for the special use of the Shahinshah."[17]

Akbar remained heirless until 1569 when his son, who became known as Jahangir, was born in the village of Sikri in 1569. Akbar began the construction of a religious compound in honour of the Chisti saint Sheikh Salim, who had predicted the birth of Jahangir. After Jahangir's second birthday, he began the construction of a walled city and imperial palace probably to test his son's stamina. By constructing his capital at the khanqah of Sheikh Salim, Akbar associated himself with this popular Sufi order and brought legitimacy to his reign through this affiliation.[18]

The city was founded in 1571 and was named after the village of Sikri which occupied the spot before. The Buland Darwaza was built in honour of his successful campaign in Gujarat, when the city came to be known as Fatehpur Sikri - "The City of Victory". It was abandoned by Akbar in 1585 when he went to fight a campaign in Punjab. It was later completely abandoned by 1610. The reason for its abandonment is usually given as the failure of the water supply, though Akbar's loss of interest may also have been the reason since it was built solely on his whim.[19] Ralph Fitch described it as such, "Agra and Fatehpore Sikri are two very great cities, either of them much greater than London, and very populous. Between Agra and Fatehpore are 12 miles (Kos) and all the way is a market of victuals and other things, as full as though a man were still in a town, and so many people as if a man were in a market."[20]

Akbar visited the city only once in 1601 after abandoning it. William Finch, visiting it 4–5 years after Akbar's death, stated, "It is all ruinate," writing, "lying like a waste desert."[21] During the epidemic of bubonic plague from 1616 to 1624, Jahangir stayed for three months here in 1619.[22] Muhammad Shah stayed here for some time and the repair works were started again. However, with the decline of Mughal Empire, the conditions of the buildings worsened.[23]

While chasing Daulat Rao Sindhia's battalions in October 1803, Gerard Lake left the most cumbersome baggage and siege guns in the town.[24] After occupying Agra in 1803, the British established an administrative centre here and it remained so until 1850.[23] In 1815, the Marquess of Hastings ordered the repair of monuments at Sikri and Sikandra.[25] The town was a municipality from 1865 to 1904 and was later made a notified area. The population in 1901 was 7,147.[26]

Demographics

[edit]As of 2011 Indian Census, Fatehpur Sikri had a total population of 32,905, of which 17,392 were males and 15,513 were females. Population within the age group of 0 to 6 years was 5,139. The total number of literates in Fatehpur Sikri was 17,236, which constituted 52.4% of the population with male literacy of 60.4% and female literacy of 43.4%. The effective literacy rate of 7+ population of Fatehpur Sikri was 62.1%, of which male literacy rate was 71.6% and female literacy rate was 51.4%. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes population was 4,110 and 1 respectively. Fatehpur Sikri had 4936 households in 2011.[1]

Language

[edit]According to the 2011 census, 98.81% of the people identified as Hindi speakers and 1.04% as Brajbhasha speakers.[27]

Government and politics

[edit]Fatehpur Sikri is one of the fifteen Block headquarters in the Agra district. It has 52 Gram panchayats (Village Panchayat) under it.

The Fatehpur Sikri, is a constituency of the Lok Sabha, Lower house of the Indian Parliament, and further comprises five Vidhan Sabha(legislative assembly) segments:

Architecture

[edit]

Fatehpur Sikri sits on a rocky ridge, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) in length and 1 km (0.62 mi) wide, and the palace city is surrounded by a 6 km (3.7 mi) wall on three sides with the fourth bordered by a lake. The city is generally organised around this 40 m high ridge, and falls roughly into the shape of a rhombus. The general layout of the ground structures, especially the "continuous and compact pattern of gardens and services and facilities" that characterised the city leads urban archaeologists to conclude that Fatehpur Sikri was built primarily to afford leisure and luxury to its famous residents.[14]

The dynastic architecture of Fatehpur Sikri was modelled on Timurid forms and styles.[28] The city was built massively and preferably with red sandstone.[29] Gujarati influences are also seen in its architectural vocabulary and decor of the palaces of Fatehpur Sikri.[30] The city's architecture reflects both the Hindu and Muslim form of domestic architecture popular in India at the time.[31] The remarkable preservation of these original spaces allows modern archaeologists to reconstruct scenes of Mughal court life, and to better understand the hierarchy of the city's royal and noble residents.[14]

It is accessed through gates along the 5 miles (8.0 km) long fort wall, namely, Delhi Gate, the Lal Gate, the Agra Gate and Birbal's Gate, Chandanpal Gate, The Gwalior Gate, the Tehra Gate, the Chor Gate, and the Ajmeri Gate. The palace contains summer palace and winter palace for Queen Mariam-uz-Zamani commonly known as Jodha Bai.

Some of the important buildings in this city, both religious and secular are:

- Buland Darwaza: Set into the south wall of congregational mosque, the Buland Darwaza at Fatehpur Sikri is 54 metres (177 ft) high, from the ground, gradually making a transition to a human scale in the inside. The gate was added around five years after the completion of the mosque c. 1576-1577 as a victory arch, to commemorate Akbar's successful Gujarat campaign. It carries two inscriptions in the archway, one of which reads: "Isa, Son of Mariam said: The world is a bridge, pass over it, but build no houses on it. He who hopes for an hour may hope for eternity. The world endures but an hour. Spend it in prayer, for the rest is unseen".

The central portico comprises three arched entrances, with the largest one, in the centre, is known locally as the Horseshoe Gate, after the custom of nailing horseshoes to its large wooden doors for luck. Outside the giant steps of the Buland Darwaza to the left is a deep well. - Jama Masjid: It is a Jama Mosque meaning the congregational mosque and was perhaps one of the first buildings to be constructed in the complex, as its epigraph gives AH 979 (A.D. 1571–72) as the date of its completion, with a massive entrance to the courtyard, the Buland Darwaza added some five years later. It was built in the manner of Indian mosques, with iwans around a central courtyard. A distinguishing feature is the row of chhatri over the sanctuary. There are three mihrabs in each of the seven bays, while the large central mihrab is covered by a dome, it is decorated with white marble inlay, in geometric patterns.

- Tomb of Salim Chishti: A white marble encased tomb of the Sufi saint Salim Chishti (1478–1572), within the Jama Masjid's sahn (courtyard). The single-storey structure is built around a central square chamber, within which is the grave of the saint, under an ornate wooden canopy encrusted with mother-of-pearl mosaic. Surrounding it is a covered passageway for circumambulation, with carved Jalis, stone pierced screens all around with intricate geometric design and an entrance to the south. The tomb is influenced by earlier mausolea of the early 15th century Gujarat Sultanate period. Other striking features of the tomb are white marble serpentine brackets, which support sloping eaves around the parapet.

On the left of the tomb, to the east, stands a red sandstone tomb of Islam Khan I, son of Shaikh Badruddin Chishti and grandson of Shaikh Salim Chishti, who became a general in the Mughal army in the reign of Jahangir. The tomb is topped by a dome and thirty-six small domed chattris and contains a number of graves, some unnamed, all male descendants of Shaikh Salim Chishti. - Diwan-i-Aam: Diwan-i-Aam or Hall of Public Audience, is a building typology found in many cities where the ruler meets the general public. In this case, it is a pavilion-like multi-bayed rectangular structure fronting a large open space. South west of the Diwan-i-Am and next to the Turkic Sultana's House stand Turkic Baths.

- Diwan-i-Khas: the Diwan-i-Khas or Hall of Private Audience, is a plain square building with four chhatris on the roof. However it is famous for its central pillar, which has a square base and an octagonal shaft, both carved with bands of geometric and floral designs, further its thirty-six serpentine brackets support a circular platform for Akbar, which is connected to each corner of the building on the first floor, by four stone walkways. It is here that Akbar had representatives of different religions discuss their faiths and gave private audience.

- Ibadat Khana: (House of Worship) was a meeting house built in 1575 by the Mughal Emperor Akbar, where the foundations of a new Syncretistic faith, Din-e-Ilahi were laid by Akbar.

- Anup Talao: Anup Talao was built by Raja Anup Singh Sikarwar. An ornamental pool with a central platform and four bridges leading up to it. Some of the important buildings of the royal enclave are surround by it including, Khwabgah (House of Dreams) Akbar's residence, Panch Mahal, a five-storey palace, Diwan-i-Khas(Hall of Private Audience), Ankh Michauli and the Astrologer's Seat, in the south-west corner of the Pachisi Court.

- Jodha Bai Mahal: The place of residence of Akbar's favourite and chief Rajput wife, Mariam-uz-Zamani, commonly known as Jodha Bai, shows Rajput influence and is built around a courtyard, with special care being taken to ensure privacy. It also has a Hindu temple and a tulsi math used by his Hindu wife for worship. This palace was internally connected to the khawabgah of Akbar.

- Naubat Khana: Also known as Naqqar Khana meaning a drum house, where musician used drums to announce the arrival of the Emperor. It is situated ahead of the Hathi Pol Gate or the Elephant Gate, the south entrance to the complex, suggesting that it was the imperial entrance.

- Pachisi Court: A square marked out as a large board game, the precursor to modern day Ludo game where people served as the playing pieces. Though many historians argue it to have been constructed in 17th century.

- Panch Mahal: A five-storied palatial structure, with the tiers gradually diminishing in size, until the final one, which is a single large-domed chhatri. Originally pierced stone screens faced the facade and probably sub-divided the interior as well, suggesting it was built for the ladies of the court. The floors are supported by intricately carved columns on each level, totalling to 176 columns in all.

- Birbal's House: The house of Akbar's favourite minister, who was a Hindu. Notable features of the building are the horizontal sloping sunshades or chajjas and the brackets which support them.

- Hiran Minar: The Hiran Minar, or Elephant Tower, is a circular tower covered with stone projections in the form of elephant tusks. Traditionally it was thought to have been erected as a memorial to the Emperor Akbar's favourite elephant. However, it was probably a used as a starting point for subsequent mileposts.[32]

Other buildings included Taksal (mint), Daftar Khana (Records Office), Karkhana (royal workshop), Khazana (Treasury), Hammam (Turkic Baths), Darogha's quarters, stables, caravanserai, Hakim's quarters, etc.

Transport

[edit]Fatehpur Sikri is about 39 kilometres (24 mi) from Agra. The nearest Airport is Agra Airport (also known as Kheria Airport), 40 kilometres (25 mi) from Fatehpur Sikri. The nearest railway station is Fatehpur Sikri railway station, about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) from the city centre. It is connected to Agra and neighbouring centres by road, where regular bus services are operated by UPSRTC, in addition to tourist buses and taxis.

In popular culture

[edit]In literature

[edit]In her poetical illustration to an engraving of a painting by William Purser, Futtypore Sicri (Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1833), Letitia Elizabeth Landon associates its abandonment by Akbar with 'the revenge of the dead'.[33]

Vita Sackville-West, in her novel All Passion Spent, places the key meeting between Deborah, Lady Slane, and Mr FitzGeorge, at Fatehpur Sikri.

She stood again on the terrace of the deserted Indian city looking across the brown landscape where puffs of rising dust marked at intervals the road to Agra. She leaned her arms upon the warm parapet and slowly twirled her parasol. She twirled it because she was slightly ill at ease. She and the young man beside her were isolated from the rest of the world.[34]

Salman Rushdie's novel The Enchantress of Florence is partly set in 16th century Fatehpur Sikri.[35]

Gallery

[edit]-

Buland Darwaza

-

Buland Darwaza rear view

-

King's Gate

-

Palace of Akbar's favourite consort, Queen Mariam-uz-Zamani

-

Diwan-i-Khas

-

Mariam-uz-Zamani's kitchen

-

Akbar's Harem Complex

-

Panoramic view of Fatehpur Sikri Palace

-

Fatehpur Sikri near Agra, Uttar Pradesh

-

Fatehpur Sikri near Agra in Uttar Pradesh

See also

[edit]- Lahore Fort

- Tomb of Jehangir

- Jama Masjid

- Tomb of Salim Chishti

- Ibadat Khana

- Jodha Bai Mahal

- Naubat Khana

- Buland Darwaza

- Fatehpuri Mosque

- Agra Fort

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Census of India: Fatehpur Sikri". www.censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ a b "52nd Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Fatehpur Sikri". www.tajmahal.gov.in. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Andrew Petersen (11 March 2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routlegde. p. 82. ISBN 9781134613656.

- ^ Patil, Devendrakumar Rajaram (1963). The Antiquarian Remains in Bihar. Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute. p. 75.

- ^ Hindu Shah, Muhammad Qasim. Gulshan-I-Ibrahimi. p. 223.

- ^ "Fatehpur Sikri". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "30 Years as World Heritage Site: Fatehpur Sikri". 22 March 2016. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Rezavi, Syed Ali Nadeem (2013). Sikri before Akbar. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-908256-8. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ Safvi, Rana (10 December 2017). "The secrets about Fatehpur Sikri". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ "Fatehpur Sikri, that Mughal emperor Akbar established as his capital and is now a World Heritage site, was once a "flourishing trade and Jain pilgrimage centre", a new book says.", India Times, 17 July 2013, archived from the original on 12 November 2020, retrieved 30 March 2016

- ^ "Fatehpur Sikri was once a Jain pilgrimage centre: Book", Zee News, 27 February 2013, archived from the original on 13 February 2021, retrieved 29 March 2016

- ^ "Fatehpur Sikri was once a Jain pilgrimage centre", The Free Press Journal, 28 February 2013

- ^ a b c d e Petruccioli, Attilio (1984). "The Process Evolved by Control Systems of Urban Design in the Mogul Epoch in India: The Case of Fatehpur Sikri" (PDF). Environmental Design: 18–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018 – via ARCHNET.

- ^ a b Catherine Ella Blanshard Asher (1992). Architecture of Mughal India, Part 1, Volume. Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780521267281.

- ^ Annette Susannah Beveridge (2002). Babur-nama: (Memoirs of Babur). Sang-e-Meel Publications, University of Michigan Press. p. 851. ISBN 9789693512939.

- ^ Edward James Rapson, Sir Wolseley Haig, Sir Richard Burn, Henry Dodwell, Mortimer Wheeler (1963). The Cambridge History of India, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 103.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Catherine Ella Blanshard Asher (1992). Architecture of Mughal India, Part 1, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–53. ISBN 9780521267281.

- ^ Andrew Petersen (11 March 2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routlegde. pp. 82–84. ISBN 9781134613656.

- ^ Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava (1973). Akbar the Great, Vol. III: Society and culture in 16th century India. Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 10.

- ^ Abraham Eraly (200). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 179. ISBN 9780141001432.

- ^ Abraham Eraly (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 284. ISBN 9780141001432.

- ^ a b Aniruddha Roy (2016). Towns and Cities of Medieval India: A Brief Survey. Taylor & Francis. p. 262. ISBN 9781351997317.

- ^ Randolf G. S. Cooper (2003). The Anglo-Maratha Campaigns and the Contest for India: The Struggle for Control of the South Asian Military Economy. Cambridge University Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780521824446.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2004). The discovery of ancient India: early archaeologists and the beginnings of archaeology. Permanent Black. p. 185. ISBN 9788178240886.

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series, Volume 24, Issue 1. Superintendent of Government Print. 1908. p. 415.

- ^ "C-16 Population By Mother Tongue - Town level". censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Markus Hattstein, Peter Delius (2000). Islam: Art and Architecture. Könemann. p. 466.

- ^ Moritz Herrmann (2011). Mughal Architecture. GRIN Verlag. p. 3. ISBN 9783640930036.

- ^ Ebba Koch (1991). Mughal Architecture: An Outline of Its History and Development (1526-1858). Prestel. p. 60.

- ^ Catherine Ella Blanshard Asher (1992). Architecture of Mughal India, Part 1, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780521267281.

- ^ Wright, Colin. "General view of the Hiran Minar, Fatehpur Sikri". www.bl.uk. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1832). "poetical illustration". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1833. Fisher, Son & Co. Archived from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1832). "picture". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1833. Fisher, Son & Co. Archived from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ From All Passion Spent (Hogarth Press,1931)

- ^ Choudhury, Chandrahas (18 April 2008). "An ode to adolescent fantasy". Mint. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Latif, Muḥammad (1896). Agra, Historical & Descriptive. Calcutta Central Press.

- Fazl, Abul (1897–1939). The Akbarnama (Vol. I-III). Translated by H. Beveridge. Calcutta: Asiatic Society. Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- Keene, Henry George (1899). "Fatehpur Sikri". A Handbook for Visitors to Agra and Its Neighbourhood (Sixth ed.). Thacker, Spink & Co. p. 53.

- Malleson, G. B., Colonel (1899). Akbar and the rise of the Mughal Empire. Rulers of India series. Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Havell, E. B. (1904). A handbook to Agra and the Taj, Sikandra, Fatehpur-Sikri and the neighbourhood (1904). London: Longmans, Greens & Co.

- Garbe, Dr.Richard von (1909). Akbar – Emperor of India. A picture of life and customs from the sixteenth century. Chicago: The Opencourt Publishing Company.

- Smith, Vincent Arthur (1917). Akbar the Great Mogul, 1542-1605. Oxford at The Clarendon Press.

- Hussain, Muhammad Ashraf (1947). A Guide To Fatehpur Sikri. The Manager, Government of India Press.

- Rezavi, S. Ali Nadeem (1998). Exploring Mughal Gardens at Fathpur Sikri. Indian History Congress.

- Petruccioli, Attilio (1992). Fatehpur Sikri. Ernst & Sohn.

- Rizvi, Athar Abbas (2002). Fatehpur Sikri (World heritage series). Archaeological Survey of India. ISBN 81-87780-09-6.

- Rezavi, Syed Ali Nadeem (2002). "Iranian Influence on Medieval Indian Architecture", The Growth of Civilizations in India and Iran. Tulika.

- Jain, Kulbhushan (2003). Fatehpur Sikri: where spaces touch perfection. VDG. ISBN 3-89739-363-8.

- Rezavi, Dr. Syed Ali Nadeem (2008). Religious Disputation and Imperial Ideology: The Purpose and Location of Akbar's Ibadatkhana. SAGE Publications.

- Havell, E. B. (1904). A handbook to Agra and the Taj, Sikandra, Fatehpur-Sikri and the neighbourhood (1904). Longmans, Greens & Co., London.

- Smith, Vincent Arthur (1917). Akbar the Great Mogul, 1542-1605. Oxford at The Clarendon Press.

- Asher, Catherine Ella Blanshard (1992). "Age of Akbar". Architecture of Mughal India, (Part 1). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26728-5.

- Fatehpur Sikri, Detailed study Arch Net Digital Library

External links

[edit]- Fatehpur Sikri

- Forts in Uttar Pradesh

- World Heritage Sites in India

- History of Uttar Pradesh

- Mughal gardens in India

- Mughal architecture

- Former capital cities in India

- Former populated places in India

- Cities and towns in Agra district

- Buildings and structures in Agra district

- Sandstone buildings in India

- Royal residences in India

- Tourist attractions in Agra district

- Archaeological sites in Uttar Pradesh

- Archaeological monuments in Uttar Pradesh

- Populated places established in 1571

- 1571 in India

- Akbar

- 1570s establishments in India

- 1571 establishments in Asia

- 16th-century establishments in the Mughal Empire

- Agra district

- Caravanserais in India