Naval Air Station Pensacola

This article's lead section may be too long. (October 2023) |

| Naval Air Station Pensacola | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Forrest Sherman Field | |||||||||||

| Near Pensacola, Florida in United States | |||||||||||

F/A-18E Super Hornets of the US Navy's Blue Angels conducting a pitchup-break over their home at NAS Pensacola in January 2021 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Location in Florida | |||||||||||

| Coordinates | 30°21′09″N 087°19′04″W / 30.35250°N 87.31778°W | ||||||||||

| Type | Naval air station | ||||||||||

| Site information | |||||||||||

| Owner | Department of Defense | ||||||||||

| Operator | US Navy | ||||||||||

| Controlled by | Navy Region Southeast | ||||||||||

| Condition | Operational | ||||||||||

| Website | Official website | ||||||||||

| Site history | |||||||||||

| Built | 1913 | ||||||||||

| In use | 1913 – present | ||||||||||

| Events |

| ||||||||||

| Garrison information | |||||||||||

| Current commander | Captain Chandra Newman | ||||||||||

| Garrison | Training Air Wing Six | ||||||||||

| Airfield information | |||||||||||

| Identifiers | IATA: NPA, ICAO: KNPA, FAA LID: NPA, WMO: 722225 | ||||||||||

| Elevation | 28 feet (8.5 m) AMSL | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Source: Federal Aviation Administration[1] | |||||||||||

Naval Air Station Pensacola or NAS Pensacola (IATA: NPA, ICAO: KNPA, FAA LID: NPA) (formerly NAS/KNAS until changed circa 1970 to allow Nassau International Airport, now Lynden Pindling International Airport, to have IATA code NAS), "The Cradle of Naval Aviation", is a United States Navy base located next to Warrington, Florida, a community southwest of the Pensacola city limits. It is best known as the initial primary training base for all U.S. Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard officers pursuing designation as naval aviators and naval flight officers, the advanced training base for most naval flight officers, and as the home base for the United States Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron, the precision-flying team known as the Blue Angels.

The station is listed as the Pensacola Station Census Designated Place (CDP) under the 2020 census and had a resident population of 5,532. It is part of the Pensacola—Ferry Pass—Brent, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Because of contamination by heavy metals and other hazardous materials during its history, it is designated as a Superfund site needing environmental cleanup.[2]

The air station also hosts the Naval Education and Training Command (NETC) and the Naval Aerospace Medical Institute (NAMI), the latter of which provides training for all naval flight surgeons, aviation physiologists, and aerospace experimental psychologists.

With the closure of Naval Air Station Memphis in Millington, Tennessee, and the transition of that facility to Naval Support Activity Mid-South, NAS Pensacola also became home to the Naval Air Technical Training Center (NATTC) Memphis, which relocated to Pensacola and was renamed NATTC Pensacola. NATTC provides technical training schools for nearly all enlisted aircraft maintenance and enlisted aircrew specialties in the U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Coast Guard. The NATTC facility at NAS Pensacola is also home to the USAF Detachment 1, a geographically separated unit (GSU) whose home unit is the 359th Training Squadron located at nearby Eglin AFB. Detachment 1 trains over 1,100 airmen annually in three structural maintenance disciplines: low observable, non-destructive inspection, and aircraft structural maintenance.

NAS Pensacola contains Forrest Sherman Field, home of Training Air Wing SIX (TRAWING 6), providing undergraduate flight training for all prospective naval flight officers for the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, and flight officers/navigators for other NATO/Allied/Coalition partners. TRAWING SIX consists of the Training Squadron 4 (VT-4) "Warbucks", Training Squadron 10 (VT-10) "Wildcats" and Training Squadron 86 (VT-86) "Sabrehawks," flying the T-45C Goshawk and T-6A Texan II.

A select number of prospective U.S. Air Force navigator/combat systems officers, destined for certain fighter/bomber or heavy aircraft, were previously trained via TRAWING SIX, under VT-4 or VT-10, with command of VT-10 rotating periodically to a USAF officer. This previous track for USAF navigators was termed Joint Undergraduate Navigator Training (JUNT). Today, all USAF Undergraduate CSO Training (UCSOT) for all USAF aircraft is consolidated at NAS Pensacola as a strictly USAF organization and operation under the 479th Flying Training Group (479 FTG), an Air Education and Training Command (AETC) unit. The 479 FTG is a tenant activity at NAS Pensacola and a GSU of the 12th Flying Training Wing (12 FTW) at Randolph AFB, Texas. The 479 FTG operates USAF T-6A Texan II and T-1A Jayhawk aircraft.

Other tenant activities include the United States Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron, the Blue Angels, flying F/A-18 Super Hornets and a single USMC C-130T Hercules; and the 2nd German Air Force Training Squadron USA (German: 2. Deutsche Luftwaffenausbildungsstaffel USA – abbreviated "2. DtLwAusbStff"). A total of 131 aircraft operate out of Sherman Field, generating 110,000 flight operations each year.

The National Naval Aviation Museum (formerly known as the National Museum of Naval Aviation), the Pensacola Naval Air Station Historic District, the National Park Service-administered Fort Barrancas and its associated Advance Redoubt, and the Pensacola Lighthouse and Museum are all located at NAS Pensacola, as is the Barrancas National Cemetery.

History

[edit]The site now occupied by NAS Pensacola has been controlled by varying nations. In 1559, Spanish explorer Don Tristan de Luna founded a colony on Santa Rosa Island, considered the first European settlement of the Pensacola area. The Spanish built the wooden Fort San Carlos de Austria on this bluff in 1697–1698. Although besieged by Indians in 1707, the fort was not taken. Spain was competing in North America with the French, who settled lower Louisiana and the Illinois Country and areas to the North. The French destroyed this fort when they captured Pensacola in 1719. After Great Britain defeated the French in the Seven Years' War and exchanging some territory with Spain, British colonists took over this site and West Florida in 1763.

In 1781, as an ally of the American rebels during the American Revolutionary War, the Spanish captured Pensacola. Britain ceded West Florida to Spain following the war. The Spanish completed the fort San Carlos de Barrancas in 1797.[3][4] Barranca is a Spanish word for bluff, the natural terrain feature that makes this location ideal for the fortress.

Pensacola was taken by General Andrew Jackson in November 1814 during the War of 1812 between Great Britain and the United States. British forces destroyed Fort San Carlos as they swept through the area. The Spanish remained in control of the region until 1821, when the Adams-Onís Treaty confirmed the purchase of Spanish Florida by the United States, and Spain ceded this territory to the US.

In 1825, the US designated this area for the Pensacola Navy Yard and Congress appropriated $6,000 for a lighthouse. Operational that year, it "is said to be haunted by a light keeper murdered by his wife."[5] Fort Barrancas was rebuilt, 1839–1844, the U.S. Army deactivating it on 15 April 1947. Designated a National Historic Site (NHL) in 1960, control of the site was transferred to the National Park Service in 1971. After extensive restoration during 1971–1980, Fort Barrancas was opened to the public. It has a visitor's center.[5]

Navy Yard

[edit]Realizing the advantages of the Pensacola harbor and the large timber reserves nearby for shipbuilding, in 1825 President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of the Navy Samuel Southard made arrangements to build a Navy Yard on the southern tip of Escambia County, where the air station is today. Navy captains William Bainbridge, Lewis Warrington, and James Biddle selected the site on Pensacola Bay.

Civilian employment

[edit]Civilian employment began in April 1826, with the construction of the first buildings at the Pensacola Navy Yard, also known as the Warrington Navy Yard. Pensacola would later become one of the best equipped naval stations in the country, but the early navy yard was beset with recruitment and labor problems. Skilled workers were simply unavailable locally, housing limited, and living conditions in Pensacola rough. At first, skilled tradesmen were recruited from Boston and other northern naval bases. Many of these new civilian employees were dissatisfied with local conditions and especially their wages and hours. As a result, on 14 March 1827 was the first labor strike. Captain Melancthon Taylor Woolsey was able to make sufficient adjustments to the workday that the men returned to work after a couple of days.[6]

One factor that inhibited both military and civilian workers from remaining in Pensacola was the lack of an adequate hospital. On 3 November 1828, naval surgeon Isaac Hulse, physician in charge of the Naval Hospital in Barrancas, wrote Commodore Melanchthon Taylor Woolsey a status report. His account covers the period of March to November 1828 and details the 66 sailors and marines admitted, their names and rank, diagnosis or the nature of their injury, and the date of their discharge or death. Mortality at Pensacola would remain high due to the prevalence of yellow fever and malaria. Many naval officers and men considered the Navy Yard an unhealthy and potentially lethal assignment. For example, Naval Constructor Samuel Keep, writing to his brother in July 1826, stated emphatically, "I shall not remain here unless I am obliged to do so."[7] Despite heroic efforts by the medical community, yellow fever would revisit the navy yard intermittently, e.g. in 1835, 1874, 1882, etc., the disease only coming under control with the work of Major Walter Reed in 1901.[citation needed]

From its foundation until the Civil War, enslaved labor was extensively utilized at Pensacola Navy Yard.[8] In May 1829, the monthly Pensacola Navy Yard list of mechanics and laborers enumerates a total of 87 employees, of whom 37 were enslaved laborers.[9] Pensacola Navy Yard was built with enslaved labor. Captain Lewis Warrington, the first commandant of the Pensacola Navy Yard, complained to the Board of Navy Commissioners, "neither laborers nor mechanics are to be obtained here." As early as April 1826, Warrington had requested and received permission to hire enslaved labor, "for I would recommend the employment of black laborers in preference to white, as they suit this climate better, are less liable to change, more easily controlled, more temperate, and more will actually do more work."[10] Even after Warrington was finally able to get skilled white journeymen mechanics from Norfolk, he asked for and received permission to continue utilizing enslaved labor, since due to the unhealthy conditions and poor pay white laborers simply would not remain at the new naval station. As a consequence, Pensacola Navy agent Samuel R. Overton advertised for 38 enslaved workers, promising local slaveholders "17 dollars per month with common Navy Rations."[11] The bondsmen's names are found on the May 1829 list of navy yard employees.[12] To allay slaveholder concerns, Commandant William Compton Bolton advertised that enslaved workers would have the benefit of medical attention at no charge at the shipyard hospital.[13]

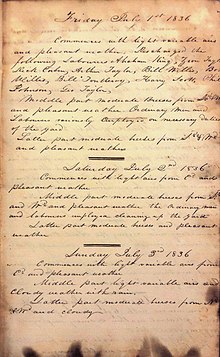

Pensacola was not the first to use enslaved labor; Washington Navy Yard, established in 1799, and soon after, Gosport Navy Yard in Virginia, both employed enslaved labor. The enslaved quickly "constituted a majority of the employees at the shipyard. They performed nearly every task required including ship construction and repair, carpentry, blacksmithing, bricklaying and general labor."[14] While not explicitly stated in Pensacola Navy Yard log entries, enslaved black workers were listed as "laborers" while white workers were categorized as belonging to "the ordinary" (see thumbnail: station log entries, 1 July 1836).[15][16]

Slavery remained integral to the Pensacola Navy Yard workforce throughout the antebellum period. As late as June 1855, the navy yard payroll listed 155 slaves.[17] Scholar Ernest Dibble concludes his study of the military presence in Pensacola with this coda: "In Pensacola the military was not just the most important single force creating the local economy, but also the most important single influence to the spread of the slaveocracy in Pensacola."[18] The civilian payrolls of Pensacola reveal that the navy yard leased slaves from prominent members of Pensacola society.[19][20] Enslaved labor continued on at the Pensacola Navy Yard until the American Civil War.[21]

On 13 August 1859, Commandant James K. McIntosh wrote to the secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey, "I have the honor to report that the steam sloop of war USS Pensacola was successfully launched ..." with this "launching the Pensacola naval facility became a true navy yard." This was followed by the sloop USS Seminole that same year.[22]

In its early years, the garrison of the West Indies Squadron dealt mainly with the suppression of the African slave trade and piracy in the Gulf and Caribbean. The US and Great Britain had outlawed the international slave trade effective 1808, but smuggling continued for decades, especially as Cuba and certain South American nations continued with slavery.

On 12 January 1861, just prior to the commencement of the Civil War, the Warrington Navy Yard surrendered to secessionists.[23] When Union forces captured New Orleans in 1862, Confederate troops, fearing attack from the west, retreated from the Navy Yard and reduced most of the facilities to rubble. At the time, they also abandoned Fort Barrancas and Fort McRee.

After the war, the ruins at the yard were cleared away and work was begun to rebuild the base. Many of the present structures on the air station were built during this period, including the stately two- and three-story houses on North Avenue. In 1906, many of these newly rebuilt structures were destroyed by a great hurricane and storm surge.

The Pensacola and Fort Barrancas Railroad was constructed in 1870 during the Reconstruction era, bringing rail service aboard the Navy Yard, and improving connections to the city of Pensacola. The company was incorporated by a special act of the State of Florida on 12 February 1870 to improve infrastructure, and was granted an easement by Congress to run through the federal Navy Yard reservation on 30 January 1871.[24]

Naval aeronautical station

[edit]

The Navy Department awakened to the possibilities of naval aviation through the efforts of Captain Washington Irving Chambers; he prevailed upon Congress to include in the Naval Appropriation Act enacted in 1911–12 a provision for aeronautical development. Chambers was ordered to devote all of his time to naval aviation.

In October 1913, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, appointed a board, with Captain Chambers as chairman, to make a survey of aeronautical needs and to establish a policy to guide future development. One of the board's most important recommendations was the establishment of an aviation training station in Pensacola.

On 20 January 1914, LCdr. Henry C. Mustin, Naval Aviator No. 11, and Lt. John H. Towers, Naval Aviator No. 3, and Lt. Patrick N. L. Bellinger, Naval Aviator No. 8, arrived in Pensacola on the former battleship USS Mississippi with the men and aircraft from the Naval Aviation Camp at Annapolis, Maryland. "The aviation unit consisted of nine officers, 23 enlisted men, and seven aircraft."[25] The first flight occurred on 2 February 1914, with Lt. Towers and Ens. Godfrey deC. Chevalier, Naval Aviator No. 7, at the controls.

Upon the entry of the United States into World War I on 6 April 1917, Pensacola, still the only naval air station, had 38 naval aviators, 163 enlisted men trained in aviation support, and 54 fixed-wing aircraft. Two years later, by the signing of the armistice in November 1918, the air station, with 438 officers and 5,538 enlisted men, had trained 1,000 naval aviators. At war's end, seaplanes, dirigibles, and free kite balloons were housed in steel and wooden hangars stretching a mile down the air station beach.

In the years following World War I, aviation training slowed down. An average of 100 pilots were graduating annually from the 12-month flight course. This was before the category of aviation cadets was established; officers were accepted for the flight training program only after at least two years of sea duty. The majority were Annapolis graduates, although a few reserve officers and enlisted men also graduated. Naval Air Station Pensacola became known as the "Annapolis of the Air".

Station Field was created on the north side of the navy yard in 1922. Enlarged, it was renamed Chevalier Field in 1935 for Lt. Cdr. Godfrey DeCourcelles Chevalier, a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy in 1910, and an early Naval Air Pilot, designated as No. 7 on 7 November 1915. With the advent of jet aviation, its 3,100-foot runway was too short for new aircraft entering service. Forrest Sherman Field was opened in 1954 for most fixed-wing operations.

Naval air station

[edit]With the inauguration in 1935 of the cadet training program, activity at Pensacola again expanded. When Pensacola's training facilities could no longer accommodate the ever-increasing number of cadets accepted by the Navy, two more naval air stations were created—one in Jacksonville, Florida, and the other in Corpus Christi, Texas. (During this period, the Southern Democratic block exerted considerable influence in Congress, as the South was a one-party region. Democrats occupied key committee chairman positions by seniority and directed many projects to their region.)

In August 1940, a larger auxiliary base, Saufley Field, named for LT R.C. Saufley, Naval Aviator 14, was added to Pensacola's activities. In October 1941, a third field, Ellyson Field, named after CDR Theodore G. "Spuds" Ellyson, the Navy's first aviator, was added.

With the start of World War II, NAS Pensacola once again became the hub of air training activities. NAS Pensacola expanded again, training 1,100 cadets a month, 11 times the number trained annually in the 1920s. The growth of NAS Pensacola from 10 tents to the world's greatest naval aviation center was emphasized by then-Senator Owen Brewster's statement: "The growth of naval aviation during World War II is one of the wonders of the modern world."[citation needed] Naval aviators from NAS Pensacola were called upon to train the Doolittle Raiders at Eglin Field in 1942 for carrier take-offs in their B-25 Mitchell bombers. Navy Lt. Henry Miller supervised their takeoff training and accompanied the crews to the launch. For his efforts, Lt. Miller is considered an honorary member of the Raider group.[26]

During the Korean War, the military was caught in the midst of transition from propellers to jets. The air station had to revise its courses and training techniques. NAS Pensacola produced 6,000 aviators from 1950 to 1953.

Forrest Sherman Field was opened in 1954 on the western side of NAS Pensacola. This jet airfield was named after the late Admiral Forrest P. Sherman, a former chief of naval operations. Shortly thereafter the United States Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron, the Blue Angels, relocated from NAS Corpus Christi, Texas.

Pilot training requirements shifted upward to meet the demands for the Vietnam War, which occupied much of the 1960s and 1970s. From a low of 1,413 in 1962, before the entry of the U.S. in any substantive way, pilot training in 1968 produced 2,552 graduates.

Naval aviation depot

[edit]From the earliest days of naval aviation at Pensacola, an aircraft maintenance facility operated at the air station. Initially known as the Construction and Repair Department, in 1923 it was redesignated an Assembly and Repair Department, and in 1948 to the Overhaul and Repair Department. In 1967, the status of the facility at NAS Pensacola and at five other Navy and one Marine Corps air stations were changed to that of separate commands, each called a Naval Air Rework Facility and directed to report to the commander of the Naval Air Systems Command instead of the air station commanding officer. Former seaplane hangars along the south edge of the air station, as well as a large structure at Chevalier Field were utilized for aircraft overhauls, and Pensacola was a designated as an A-4 Skyhawk rework site.

In 1987 the name Naval Aviation Depot replaced the name Naval Air Rework Facility to more accurately reflect the range of their activities. Three Naval Aviation Depots were closed under the 1993 BRAC Committee recommendations including that at NAS Pensacola, and most of the buildings on the air station involved in these tasks razed.[27]

Naval Photography School

[edit]

The Naval Photography School was located at base. Howard Zieff learned photography there and the monthly inspection at the school was photographed by Joseph Janney Steinmetz in 1944. The Naval Photographic School trained Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard students in basic (A School), advanced (B and C Schools), and special curriculum (Reconnaissance, Photojournalism, etc.) It was housed in BlDG 1500, now the base headquarters, and a small museum has a variety of items from the school.[28]

Modern history

[edit]In 1971, NAS Pensacola was picked as the headquarters site for CNET (Chief of Naval Education and Training), a new command which combined direction and control of all Navy education and training activities and organizations. The Naval Air Basic Training Command was absorbed by the Naval Air Training Command, which moved to NAS Corpus Christi, Texas. In 2003, CNET was replaced by the Naval Education and Training Command (NETC).[29]

Also located on board NAS Pensacola is Naval Aviation Schools Command (NAVAVSCOLSCOM). This command has the following subordinate schools:

- Aviation Enlisted Aircrew Training School (AEATS)

- AETAS is also known as Naval Aircrew Candidate School (NACCS)

- Naval Aviation Technical Training Center (NATTC)

- NATTC is composed of "A" schools for training of enlisted personnel in various aviation support disciplines including: ground support equipment operators, aviation ordnancemen, aircraft powerplant mechanics, fixed and rotary wing structural airframe mechanics, avionics technicians, aircraft electricians, aviation command and control electronics maintenance personnel, expeditionary airfield construction personnel, air traffic controllers, flight equipment technicians, enlisted aircrew, and parachute riggers. Courses in these disciplines are attended by both Navy personnel and U.S. Marines. Marines aboard NAS Pensacola training for or teaching courses in the aforementioned jobs belong to Marine Air Training Support Group 23 (MATSG-23), which consists of both Aviation Maintenance Squadron 1 (AMS-1) and AMS-2.

- Crew Resource Management

- U.S. Navy and Marine Corps School of Aviation Safety

NAVAVSCOLSCOM also previously oversaw Aviation Officer Candidate School (AOCS) until that program's disestablishment and merger into Officer Candidate School (OCS) under Officer Training Command at NETC Newport, Rhode Island in 2007.

The Pensacola Naval Complex in Escambia and Santa Rosa counties employs more than 16,000 military and 7,400 civilian personnel.

During the 2005 round of Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC), people in Florida and the Navy feared that NAS Pensacola might be closed, despite its naval hub status, due to extensive damage by Hurricane Ivan in late 2004. Nearly every building on the installation had suffered heavy damage, with near total destruction of the air station's southeastern complex. The main barracks, Chevalier Hall, did not reopen until late January 2005, four months after the storm. When the list was released on 13 May 2005, NAS Pensacola and other military bases hit by Ivan in Northwest Florida were not on the BRAC list. Their facilities were rebuilt.

In May 2006, Navy construction crews unearthed a Spanish ship during an archeological excavation. It may date to the mid-16th century. The ship remains were discovered during the rebuilding of the base's rescue swimmer school, which was destroyed by Hurricane Ivan.[30]

On March 3, 2010 the commander of the base, Captain William Reavey Jr., was relieved of command after a Navy investigation into alleged improper conduct. Reavey was replaced by Captain Christopher Plummer.[31]

United States Air Force at NAS Pensacola

[edit]NAS Pensacola is host to the 479th Flying Training Group (479 FTG) of the Air Education and Training Command (AETC). The 479 FTG is composed of the 451st Flying Training Squadron, 455th Flying Training Squadron and 479th Operations Support Squadron. The 479 FTG is part of the 12th Flying Training Wing at Randolph AFB, Texas, but student information and files are handled through Tyndall AFB, Florida while they train at NAS Pensacola. With the divestment of Specialized Undergraduate Navigator Training (SUNT) and the retirement of the T-43 Bobcat from the 12th Flying Training Wing main operation at Randolph AFB, the 479 FTG assumed responsibility for the renamed Undergraduate Combat Systems Officer Training (UCSOT) for all prospective USAF CSOs. The 479 FTG operates USAF T-6 Texan II and T-1 Jayhawk aircraft at NAS Pensacola.

NAS Pensacola is also home to AETC's Detachment 1, 359th Training Squadron (359 TRS). A geographically separated unit of the 359 TRS at Eglin AFB, Florida, and falls under the 82nd Training Wing (82 TRW) at Sheppard AFB, Texas. This school provides enlisted technical training for all USAF Aircraft Structural Maintenance (ASM), Low Observable (LO) Aircraft Structural Maintenance, and Non-Destructive Inspections (NDI) students. The 359 TRS, Det 1, graduates approximately 1200 students annually.

The USAF's Detachment 2, 66th Training Squadron (a geographically separated part of the 336th Training Group's Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) school at Fairchild Air Force Base) was located here at NAS Pensacola, dedicated to aircrew parachute water survival training, but relocated to Fairchild AFB in August 2015.[32]

Incidents and accidents

[edit]

On 20 February 1939, a squadron of twelve U.S. Navy aircraft, described as "fast combat ships", were returning to NAS Pensacola, Florida, from a routine training trip and found the Gulf Coast socked in by a fog described as one of the heaviest ever witnessed in the region. Eight planes were lost with two pilots killed. Three aircraft piloted by instructors, and one other plane, were diverted by radio and outran the fogbank to land safely at Atmore and Greenville, Alabama.

Six of the Navy's flying students bailed out in the darkness and reached ground safely in their first parachute jumps. Their planes were wrecked beyond repair. Lt. G. F. Presser, Brazilian Navy flyer, in training at the Naval Air Station, crashed and was killed at Corry Field. His plane burned. The fog was so dense that the intense glow of the burning plane could not be seen by attendants on the field. Lt. N. M. Ostergren, U.S. Navy, was found dead at his crashed plane near McDavid the next morning. Officers said the wreckage of the eight planes – they declined to estimate their worth, but aviation circles here said the fast combat ships would cost from $18,000 to $20,000 each – was the air station's second heaviest loss. In 1926 a hurricane wrecked planes on the ground, hangars and other equipment for a total damage of about $1,000,000."[33]

The aircraft involved were all Boeing F4B-4 fighters. These included BuNos. A9014, A9040, 9242, 9243, 9258, and 9719.[34]

On December 6, 2019, a terror attack occurred at the installation,[35] resulting in three deaths and several injuries. The attacker was shot and killed by law enforcement.[36]

This was the first deadly terrorist attack on U.S. soil since 9/11 that was planned abroad.[37]

See also

[edit]- Naval Air Station Pensacola shooting

- Pensacola: Wings of Gold – fictional television series set at NAS Pensacola

- List of United States Navy airfields

References

[edit]- ^ FAA Airport Form 5010 for NPA PDF

- ^ "Florida NPL/NPL Caliber Cleanup Site Summaries: Pensacola Naval Air Station 5 Year Progress Report". US Environmental Protection Agency. March 2003. Archived from the original on October 30, 2004.

- ^ "The Forts of Pensacola Bay" (history), Visit Florida Online, 2006, webpage: VFO-Forts.

- ^ "Fort San Carlos de Barrancas" (history), National Park Service (NPS), webpage: NPS-fort2.

- ^ a b Shettle, Jr., M. L., "United States Naval Air Stations of World War II, Volume I: Eastern States", Schaertel Publishing Co., Bowersville, Georgia, 1995, LCCN 94--68879, ISBN 0-9643388-0-7, p. 178.

- ^ Dibble, Ernest F., Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence, Pensacola Series Commemorating the American Revolution Bicentennial 3, Pensacola, FL: Pensacola/Escambia Development Commission, 1974 p. 13.

- ^ Sharp, John G. Naval Surgeon Isaac Hulse re his patients at Naval Hospital Barrancas, 3 November 1828 http://genealogytrails.com/fla/escambia/1827navalhosp.html

- ^ Hulse, Thomas, Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863, Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), pp. 497–539.

- ^ Sharp John G. List of Mechanics, Laborers, &c employed in the Navy Yard Pensacola May 1829 http://genealogytrails.com/fla/escambia/pnyemployees1829.html

- ^ Dibble, p. 23.

- ^ Pensacola Gazette 6 April 1827, p. 5.

- ^ Sharp May 1829 List of Mechanics

- ^ Floridian and Advocate 10 September 1836 p. 1

- ^ Clavin, Matthew J. Aiming for Pensacola Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers, Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2015, p. 84.

- ^ Sharp, John G.M. Early Pensacola Navy Yard in Letters and Documents to the Secretary of the Navy and Board of Navy Commissioners 1826-1840, Part II,http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/pensacola-sharp.html

- ^ Dibble, Ernest F. Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence, p.72.

- ^ Ericson, David F. Slavery in the American Republic Developing the Federal Government, 1791 -1861 (University of Kansas Press:Lawrence Kansas 2011), 259n55.

- ^ Dibble, Ernest F. Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence, p.67.

- ^ Hulse,Thomas Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863, Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), pp. 497–539.

- ^ Hulse, Thomas, "Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863," Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), 514 - 515.

- ^ Dibble, p. 62

- ^ Pearce, George F. The U.S. Navy in Pensacola From Sailing Ships to Naval Aviation (1825–1930) University of West Florida: Pensacola 1980 pp. 62–63.

- ^ Miller, J. Michael. "Marine's Telling of 1861 Florida Navy Yard Fall Given", Fortitudine, vol XX, no. 4 (Spring 1991): 8.

- ^ Turner, Gregg M., A Journey Into Florida Railroad History, University Press of Florida, LCCN 2007-50375, ISBN 978-0-8130-3233-7, p. 94.

- ^ Shettle, Jr., M. L., United States Naval Air Stations of World War II, Volume I: Eastern States, Schaertel Publishing Co., Bowersville, Georgia, 1995, LCCN 94--68879, ISBN 0-9643388-0-7, p. 177.

- ^ Doolittle Tokyo Raiders, Memorial site of Richard O. Joyce

- ^ United States General Accounting Office, "Closing Maintenance Depots: Savings, Workload, and Redistribution Issues", United States General Accounting Office / National Security and International Affairs Division, Washington, D.C., GAO/NSIAD-96-29, March 1996, Appendix I – History of the Services' Depot Systems, p. 62.

- ^ US Marine Corps SGT James Karney, US Naval Photography School graduate

- ^ "NETC up and Running; CNET Disestablished". Archived from the original on 2006-11-22. Retrieved 2006-10-15.

- ^ "Navy discovers centuries-old Spanish ship buried in sand". Albuquerque Tribune. June 2, 2006. Archived from the original on June 13, 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ Tilghman, Andrew, "NAS Pensacola CO's firing made permanent", Military Times, March 4, 2010.

- ^ Parachute water survival moves to Fairchild

- ^ Crestview, Florida, "8 Planes Wrecked In Fog – Two Lose Lives As Eight Planes Wreck At Air Station", Okaloosa News-Journal, 24 February 1939, Volume 25, Number 8, p. 1.

- ^ "US Navy & US Marine Corps Aircraft Accidents 1920 to 1955". Accident-report.com. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ^ Fieldstadt, Elisha (December 6, 2019). "Shooting at Naval Air Station Pensacola; at least 2 dead, multiple injured". NBC News. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ By T.S. Strickland, Brittany Shammas, Alex Horton and Kim Bellware Dec. 6, 2019 WashingtonPost.com

- ^ Friedman, Thomas L. (26 May 2020). "Opinion | Mike Pompeo is the Worst Secretary of State Ever". The New York Times.

Bibliography

[edit]- FAA Airport Form 5010 for NPA PDF

- Clavin,Matthew J. Aiming for Pensacola Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2015, p. 84.

- Dibble, Ernest F., Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence, Pensacola Series Commemorating the American Revolution Bicentennial 3, Pensacola, FL: Pensacola/Escambia Development Commission, 1974 p. 62

- Hulse, Thomas, Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863, Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), pp. 497–539.

- Keillor, Maureen Smith, and Keillor, AMEC (SW/AW) Richard. Naval Air Station Pensacola. Arcadia Publishing, 13 January 2014. ISBN 9781467111010

- Pearce, George F. The U.S.Navy in Pensacola From Sailing Ships to Naval Aviation (1825–1930) University of West Florida: Pensacola 1980.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- List of Mechanics, Laborers, &c employed in the Navy Yard Pensacola, May 1829 (Genealogy Trails History Group)

- Pensacola Naval Hospital Records, November 1828 (Genealogy Trails History Group)

- Resources for this U.S. military airport:

- FAA airport information for NPA

- AirNav airport information for KNPA

- ASN accident history for NPA

- NOAA/NWS latest weather observations

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KNPA

- Airports in Florida

- Transportation buildings and structures in Escambia County, Florida

- Military installations in Florida

- Military Superfund sites

- Naval aviation education

- Pensacola, Florida

- United States Naval Air Stations

- Buildings and structures in Escambia County, Florida

- Superfund sites in Florida

- 1913 establishments in Florida

- Overseas or abroad military installations

- Military installations established in 1913

- Training establishments of the German Air Force